You Can't See It, It's Electric...

On the back of Nvidia's most recent chip announcement, I wanted to highlight some of the upcoming challenges and opportunities in AI. Let's dig in...

In our view, Fed days have multiple markets gyrations: there is the calm before the meeting; the official announcement reaction; press release volatility; and then overnight digestion and possibly a reversal tomorrow.

Despite the fact that the Fed has raised rates considerably, the bottom line is that growth and employment have been resilient.

While we have argued that one reason for this has been “stealth liquidity,” another reason has been the investment in and excitement around artificial intelligence (AI).

On Monday evening, Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s founder and CEO, announced the company’s newest achievement in chip design.

We have had several questions asking us to “simplify” the AI players and their roles in the ecosystem. While this is not an easy task, hopefully, some will find today’s note a start to answering those questions.

In “Where the Puck is Going,” (here) we began to consider the industries beyond semiconductors where AI would have an immediate impact.

Today, we will try to expand on that with a focus on the AI requirements for and sources of electricity.

“You can't see it. It's electric!

You gotta feel it. It's electric!

You gotta know it. It's electric boogie woogie, woogie.” Marcia Griffiths, Electric Slide.

1. The AI Semiconductor Value Chain

The chart below from Spear breaks down the AI Semiconductor Value Chain into “Inside the Rack” and “Outside the Rack.”

Inside the Rack are companies that design (such as Nvidia and AMD) and manufacture (such Taiwan Semiconductor) chips.

In addition, there are companies that provide critical components such as Host Memory Buffering (“HMB Memory”) and CoWoS packaging (stacking chips and packaging them onto a substrate)

Outside the rack: These are the companies that provide power and thermal management inside the data center (such as Eaton and Vertiv), as well as semi-conductor manufacturing equipment providers (such as ASML) and test and measurement tools (such as Teradyne) that are used in the manufacturing process.

While these are grouped in the chart below, they are each specialized and are trading on company-specific dynamics.

Within their verticals, some of these are near-monopolies.

(This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security, it is not investment advice).

Source: Ivana Spear. Through year-to-date 2024.

2. Power Management and Cooling - Where the Puck Is

The power consumption needs from AI reflect a significant step change from previous computing cycles. (Essentially, the theme of today’s note).

The chart below shows Evercore’s AI Power Basket relative to the Nasdaq 100 year-to-date.

While the Nasdaq 100 is up nearly 8% year-to-date, Evercore’s AI Power Basket is up 35%.

Nvidia’s newest chip designs (announced on Monday) will require greater power and cooling.

The companies included in Evercore’s AI Power Basket are: Advanced Energy Industries (ticker: AEIS); Atkor (ticker: ATKR); Constellation Energy (ticker: CEG); Eaton (ticker: ETN); Comfort Systems (ticker: FIX); Hubble (ticker: HUBB); Manpower (ticker: MPWR); NRG Energy (ticker: NRG); Nuscale Power Corp. (ticker: SMR); Trane Technologies (ticker: TT); Vertiv (ticker: VRT); and Vistra (ticker: VST).

(This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security and is not investment advice. Please do your own research).

Source: TradingView. Through year-to-date 2024.

3. What Exactly Did Nvidia Announce on Monday?

While there were a number of (very) technical announcements from Nvidia on Monday, I think what received most attention was:

the new Blackwell B100 large chip;

the GB200 super-chip (CPU+2xGPU); and

the Omniverse Cloud stack for autonomous robotics, based on new AI layers (Groot) and chip (Jetson Thor), combined by AI integrator (Osmo).

The GB200 has 208 billion transistors on a 4nm process, dwarfing the Hopper H100's 80 billion. This represents a leap from 19 to 20,000 teraflops in 8 years.

The GB200 has 3600x the computing power than its 2016 (8 years) predecessor delivered. In other words, this was quite an achievement.

To put this in perspective, Moore’s Law (the idea that Intel founder Gordon Moore posited in 1965 that the number of transistors on microchips would double every two years) would have projected 30x the computing power in 10 years.

In other words, the advancement in the GB200 chip that Nvidia announced Monday night blew away Moore’s law.

On the robotics side, the achievements were equally scary impressive. (See the video here).

This feels like a slowly and then all at once moment in AI and robotics.

There was a documentary called AlphaGo that chronicled the competition in the the ancient Chinese game Go (with more board configurations than there are atoms in the universe) between a computer and the reigning world master Lee Sedol. The AlphaGo matches were in 2016.

Sedol retired from the game in 2019 declaring AI “invincible”. (here). That was 5 years ago.

In other words, robotics and AI have been coming quickly, this week’s Nvidia announcement simply reflected acceleration.

While Monday’s announcement was interesting from a technology standpoint, in general, as we have highlighted in the past, we see $900 per share for Nvidia (30x $30 in expected earnings) as roughly the right near-term level for Nvidia shares.

Monday’s announcement, didn’t move the near-term earnings needle although some analyst’s increased their targets to the $1,000-$1,100 level.

If you hold Nvidia shares, this was not a reason to sell, but as we have said, we believe that the pace of gains in the shares will slow (hard not to given the torrid pace) and that investors can begin to consider: adjacent AI areas (like power and cooling); industries that are beneficiaries of AI; or companies that have large data sets that can help train AI.

(This is not investment advice and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security).

Source: TradingView. Through year-to-date 2024.

4. AIs Impact on Electricity Demand

“What you have today is electric demand that has been relatively flat for years now all of the sudden looking at an 81% increase” in the growth rate forecast over the next five years.”

— John Ketchum, CEO of NextEra Energy, on Monday at CERAWeek (the world's premier energy conference).

Even if he is half right, the implications for generation, transmission and storage (batteries) is incredible.

On the generation side, in 2023, the U.S. added 32.4 gigawatts of solar capacity, which shattered the 2021 record of 23.6 gigawatts. That represents 52% of all added energy capacity in the U.S., with natural gas coming in a distant second with only 18%. (see the article here).

In addition, there is increasing acceptance of nuclear as a non-carbon fuel.

From a transmission stand point, the US could use an upgrade.

The US Energy Information Association (EIA) estimates that the US loses 5% of its power generation in transmission (here).

Energy storage right now seems to be largely based on lithium batteries. Although the technology has improved, continued advancements are likely required and alternative methods may be developed.

When I consider these three components of energy (generation, transmission and storage), their commonality is the significant use of commodities.

In the case of power generation - oil, natural gas, steel for turbines, uranium (nuclear) and silicon (solar).

For transmission, I always think of copper.

And in storage lithium.

While these ideas seem obvious and with the US Inflation Reduction Act that provides Federal dollars and encouragement for clean energy, one might expect these commodities and shares in their related producers to outperform, the opposite has been true (nearly across the board).

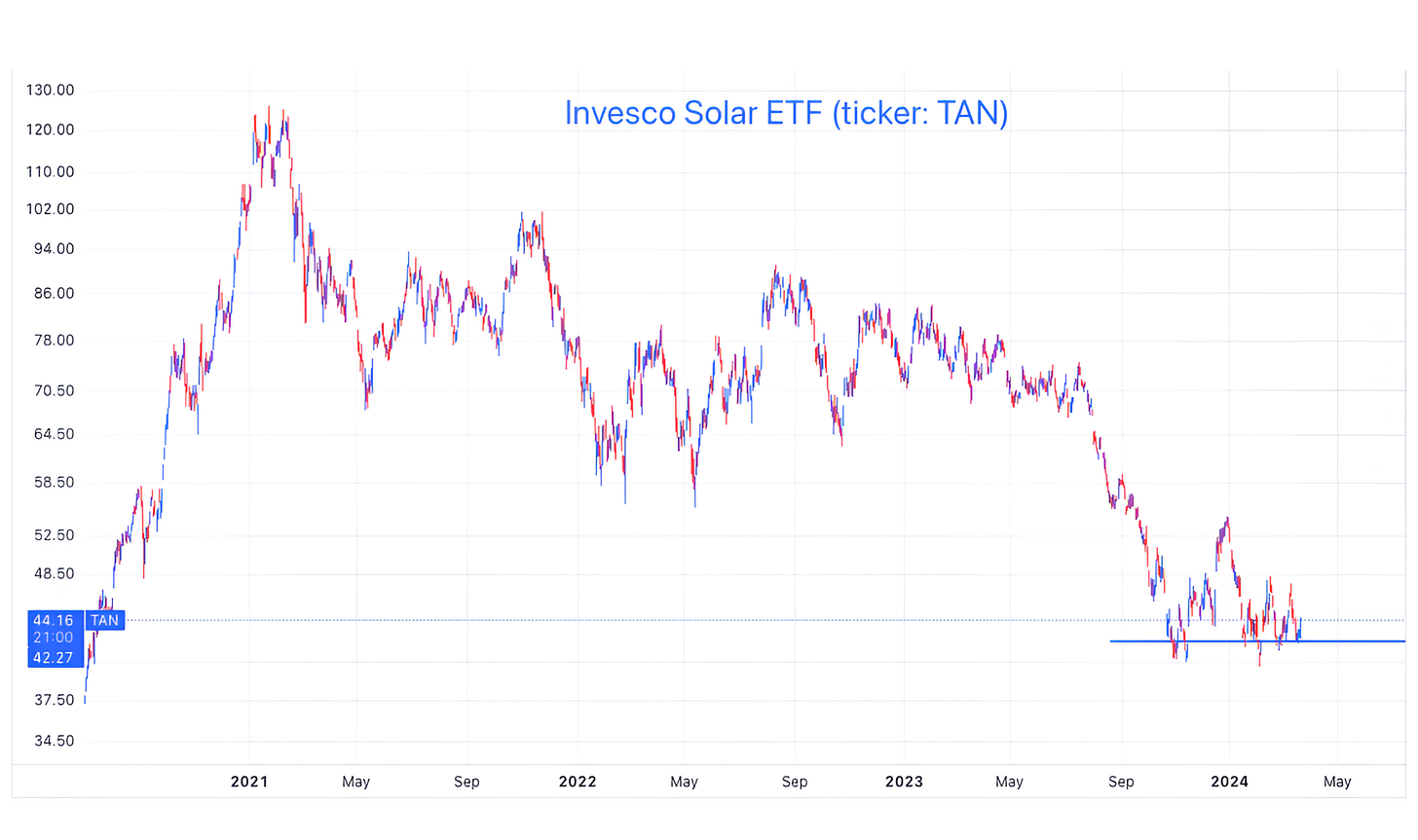

The chart below shows the Invesco Solar ETF (ticker: TAN). This ETF is comprised of those global companies that are levered to the manufacture and production of solar panels.

Since its early 2021 peak, the Solar ETF has dropped 65%.

After rallying with the expectation of the Biden Presidency, the shares dropped with the reality, despite massive stimulus for the sector.

Lithium producers and Uranium have been similarly frustrating.

On the other hand, we have recently shown some early but potentially bullish signs in Oil and Copper.

Could the rest of the the energy oriented commodities begin to rally due (at least partially) to AI?

As Jeff Currie, the former Goldman Sachs commodities specialist and current Carlyle chief strategy officer of energy pathways, recently said:

“Being short oil and commodities in a late-cycle expansion is like being short natural gas in a blizzard.”

Exactly.

(This is not a investment advice and is not recommendation to buy or sell any security)

Source: TradingView. March 17, 2024.

5. Now That’s a Buyback

In one of my earliest Finance 101 classes at business school, the professor tried to excite the class with an “a ha” moment when he showed us that share buybacks were a more efficient way to return capital to shareholders than traditional dividends.

Traditional dividends in the US are faced with taxation at the corporate level and personal level (double taxation), whereas share buybacks only face taxation at the corporate level (shares are purchased with after-tax income).

When I entered the real world, just in time to ride the wave of the dot-com bubble, companies were giving out options to employees in lieu of salaries.

Somehow, these companies had convinced investors that options were nearly free and had little (or no expense); whereas salaries - a cash obligation - were more “expensive.” The thinking was that, $1 million in options didn’t impact cash flow or earnings while $1 million in salary did.

As a result, at the time, when companies were buying back shares rather than shrinking the overall share count, the diluted shares outstanding would expand because of the options issuance.

There are three other issues with share buybacks that I identified when I entered the real world (in addition to the fact that they didn’t necessarily reduce the overall share count):

When the board announces a buyback, they don’t need to do it. They can simply say market conditions have changed.

If they do implement the buyback, there is often no set timeline. The company can execute it in a quarter, a year and may never use the whole announced amount. The “return of capital” unlike a dividend is not predictable.

There is also a “signaling” phenomena with dividends.

There are companies that increase dividends every year (“aristocrats”) and some investors like that predictability and show of strength.

On the other hand, when a company cuts its dividend, it is a signal (not always negative).

When a company trades with outsized dividend yields, I have questions. Because of the lack of transparency in share buybacks, in my view, they have less of a signaling impact than traditional dividends.

Finally, their is the tangible nature of receiving cash (regardless of double taxation) that just doesn’t exist in a buyback.

All of that said - the Apple buyback over the last 12 years (chart below) is impressive and one to behold. This buyback has been like few others.

Through a combination of cash flow and borrowing (at ultra low rates) Apple has reduced its shares outstanding by 40% since 2012.

This has helped push up the companies earning per share (fewer share outstanding) even in periods when operating income was flat to down.

This must be the type of buyback they taught be about in business school.

(This is not a investment advice and is not recommendation to buy or sell any security).